thahappycamper

Level 3

http://www.theverge.com/2014/7/22/5881501/the-unbelievable-life-and-death-of-michael-c-ruppert

The unbelievable life and death of Michael C. Ruppert

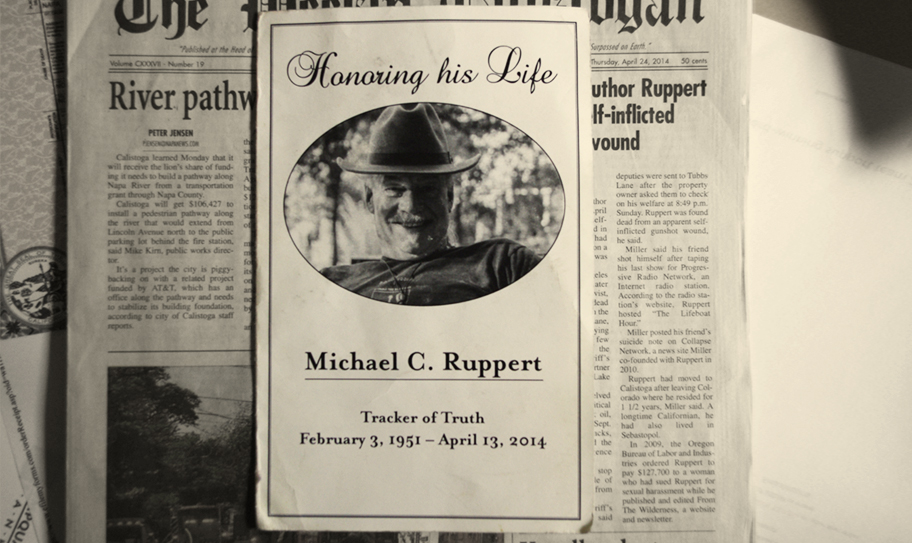

After decades of struggle, the notorious doomsayer finally found fame and recognition. Then he shot himself.

By the second Sunday of April this year, Michael C. Ruppert was broke. The 63-year-old cop-turned-writer and firebrand gained fame by starring in Collapse, a 2009 documentary in which he predicts society’s destruction. Publicity from the film was great — he went on a countrywide promotional tour — but compensation had fizzled out. By April, he was receiving just a couple hundred dollars per month in royalties to supplement his meager Social Security checks.

In an effort to simplify his life, Ruppert had gradually sold, tossed out, or given away nearly all of his possessions, which included an arsenal of guns, countless books, and government documents. All that remained was a collection of sentimental knickknacks, along with clothes appropriate for a man in his 60s: button-up shirts, dark-colored slacks, a few flannels, a couple of L.L. Bean jackets, and a gray cowboy hat. Everything he owned fit into his burgundy 2000 Lincoln Continental.

For the last eight years, Ruppert had largely lived off the goodwill of friends and followers. When he made public requests for money — either through his weekly podcast, “The Lifeboat Hour,” or in posts to more than 5,000 Facebook followers — he received checks in the mail. When he needed a place to stay, people opened their homes. And it’s no surprise why: to subscribers of his elaborate theories — that the CIA trafficked drugs; that the Bush administration was behind the 9/11 attacks; or that the human race will face extinction by 2030 — Ruppert was a soldier who fought under the banner of truth. In exchange for exposing dark secrets, he was persecuted by authorities and shadowy organizations: he’d received death threats — both explicit and covert, he said — because he knew too much.

So when he made a plea for a place to stay early this year, a follower and friend named Jack Martin in Calistoga, California, offered up a modest trailer. That’s where, on the evening of April 13th, Ruppert committed suicide with a gunshot to the head. According to Ruppert’s friends, his suicide at first seemed sudden and unexpected — a brash decision during a dark moment. But looking back over his life and final days, Ruppert’s suicide resembles a grand finale — the end of a trail he’d been following for decades.

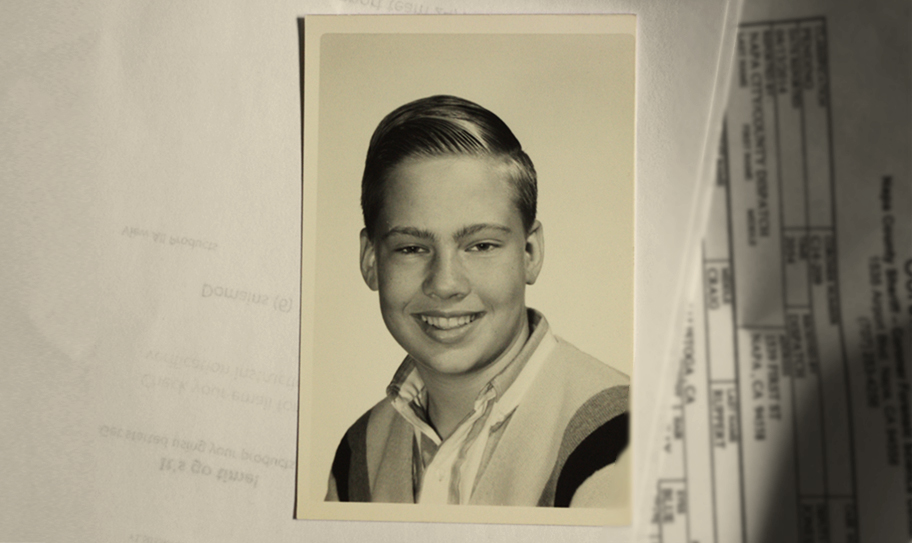

An only child, Ruppert’s family had close ties to the military and federal government. His father was a US Air Force pilot during the Second World War and later worked for Martin Marietta — which became Lockheed-Martin — "as a liaison between the CIA, the US Air Force, and Martin for booster programs," Ruppert wrote in a 2010 online autobiography.

Ruppert interviewed to be a CIA operative during his senior year at UCLA in 1973, he wrote, but turned down the subsequent offer. He became a cop with the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) and handled narcotics cases in some of the city’s most dangerous neighborhoods. The hours were long, and the job eventually got to him. He would later write that his work with the LAPD saddled him with "combat fatigue."

It was during his tenure at the LAPD that Ruppert met a woman named Nordica Theodora "Teddy" D’Orsay. Ruppert later wrote that their 15-month relationship "determined the course of my life…."

Teddy wasn’t a cop, but she and Ruppert met at a Marina del Rey cop bar in 1975. The two became infatuated with one another, and quickly moved in together. Early in their relationship, however, Ruppert became suspicious of Teddy. For a civilian, she was, he thought, a little too knowledgeable about guns and stakeouts and the day-to-day work of officers on a beat. She dropped names of LAPD cops as well as crime bosses and undercover agents.

When Teddy started staying out several nights per week and taking trips to San Francisco and Hawaii, Ruppert’s suspicions mounted. He treated Teddy as though she were a suspect in a crime. He gathered intel. It’s unclear what evidence he compiled, but Ruppert concluded that Teddy had ties to a San Francisco mobster and the shah of Iran. She grew even more distant. Then, in early 1977, she walked out on him.

After she left, Ruppert said, he became the victim of harassment: phone calls with dead silence on the other end; apartment searches while he was out; cars tailing him. He began sleeping with a gun under his pillow.

HE BECAME THE VICTIM OF HARASSMENT: PHONE CALLS WITH DEAD SILENCE ON THE OTHER END; APARTMENT SEARCHES WHILE HE WAS OUT; CARS TAILING HIM. HE BEGAN SLEEPING WITH A GUN UNDER HIS PILLOW

Ten weeks later, Teddy finally called Ruppert and said that she was in the New Orleans area. Ruppert drove to Louisiana and found her, he later wrote, "equipped with a scrambler phone and night-vision devices, and working from sealed communiqués delivered by Naval and Air Force personnel." He concluded that "she was involved in something truly ugly" — "arranging for large quantities of weapons to be loaded onto ships leaving for Iran." She was also working with "associates" of a New Orleans mafia boss bringing "large quantities of heroin into the city." Ruppert would later say that he and Teddy had even been shot at outside a New Orleans-area bar — retribution, he concluded, for discovering too much about Teddy’s covert actions. Ruppert broke off the relationship and returned home.

When he shared what he’d discovered with LAPD intelligence officers, they "promptly told me that I was crazy," he wrote. Overwhelmed, he checked himself into a psychiatric hospital for a "much-needed" monthlong rest. Though he was eventually reinstated as an officer, both his reputation and interest in the job vanished. In November 1978, he resigned. In time, Ruppert came to believe that the LAPD was part of a larger narco-trafficking network.

Through the press, Ruppert tried to expose what he’d discovered. In 1981, he made persistent calls to a Los Angeles Herald-Examiner columnist in an effort to expose Teddy’s trafficking network. The columnist ultimately published a two-part series, "The Spy Who Loved Me." But the series’ findings were, at best, inconclusive. It cited "a retired LAPD intelligence officer, another FBI agent, and [a psychiatrist]" who agreed that Ruppert’s story may have been "what he believes to be the truth," but that there was scant evidence to prove it. "Each of these three professionals professed both a measure of admiration and a measure of fear of Ruppert," the series read.

With paltry professional prospects, Ruppert drifted. He worked at a 7-Eleven, but was fired on his first day for selling alcohol to a minor. He declared bankruptcy and moved in with his parents. He developed a drinking problem. By 1984, he began attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and got sober. But he still struggled to find a new career. He told friends that he held a number of disparate jobs: as an amplifier assemblyman, a UPS driver, a gun shop clerk, a manager for a private security firm. In his spare time, he worked as a freelance writer — even landing a 1985 byline in the Los Angeles Times. In 1994, at the age of 43, Ruppert met a 23-year-old woman, Mary, at an AA meeting. The two got married — his first and only marriage — but divorced less than two years later. Distraught and aimless, he told Mary he was suicidal.

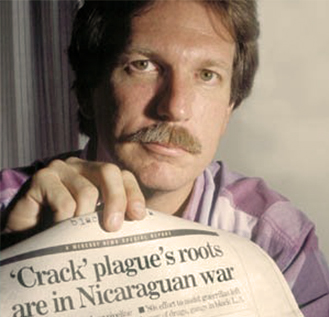

Then, Ruppert read a story that would change his life. It was a groundbreaking investigative report — a series of articles connecting the CIA to Nicaraguan drug runners. Published in August 1996 in the San Jose Mercury News, Gary Webb’s three-part series, "Dark Alliance," provided compelling evidence that drug traffickers peddled cocaine on Los Angeles streets to fund CIA-supported Contras embroiled in a Nicaraguan civil war. The series’ assertions — that CIA officials aligned themselves with criminals and "helped spark a crack explosion in urban America" — inspired protests in black communities nationwide.

HE WORKED AT A 7-ELEVEN, BUT WAS FIRED ON HIS FIRST DAY FOR SELLING ALCOHOL TO A MINOR. HE DECLARED BANKRUPTCY AND MOVED IN WITH HIS PARENTS. HE DEVELOPED A DRINKING PROBLEM

"Dark Alliance" drew harsh criticism for overreaching in its conclusions from several national outlets, including the New York Times. But that mattered little to Ruppert. In his eyes, Webb provided credible evidence that the CIA was involved in drug trafficking: "Dark Alliance" legitimized his accusations against Teddy, the CIA, and the LAPD.

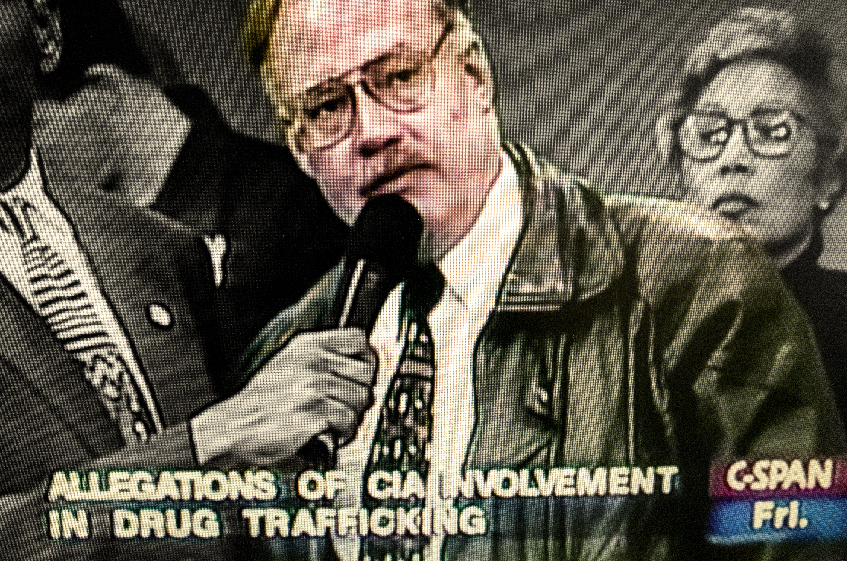

The uproar over "Dark Alliance" was also an opportunity for Ruppert to have his suspicions heard. In November 1996, CIA director John M. Deutch agreed to address the allegations in Webb’s series during a town hall meeting at a high school in South Los Angeles. The interaction was broadcast by C-SPAN, and Ruppert seized the opportunity to step into the spotlight.

"I am a former Los Angeles police narcotics detective, and I worked South-Central Los Angeles," Ruppert said into a microphone during the Q&A session in front of the jam-packed, audibly agitated, mostly African-American crowd. In the video — now legendary among Ruppert’s fans — Ruppert looks like a high-school social studies teacher, with combed-over gray hair, a manicured mustache, and wire-rimmed glasses. "I will tell you, Director Deutch," Ruppert said, "emphatically and without equivocation that the agency has dealt drugs throughout this country for a long time."

"THAT’S WHAT I DID 18 YEARS AGO, AND I GOT SHOT AT FOR IT."

The audience erupted. When the din subsided, Deutch suggested that Ruppert report his findings to the authorities. "That’s what I did 18 years ago, and I got shot at for it," Ruppert said, referencing the alleged shooting incident with Teddy outside a New Orleans-area bar.

The crowd jeered Deutch. Ruppert looked on with a satisfied grin. In a matter of minutes, he had become a heroic figure battling the CIA, willing to stare down authority.

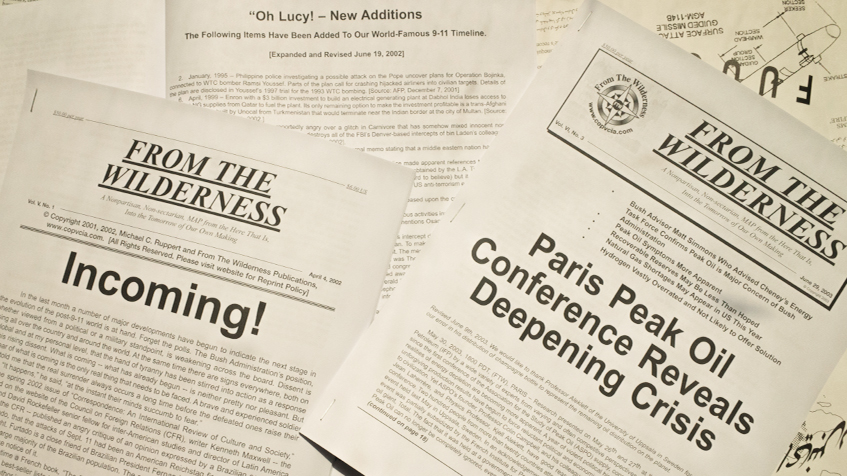

News of the confrontation spread, and Ruppert capitalized on the publicity. He started a muckraking, conspiratorial newsletter called From The Wilderness (FTW) that would eventually boast more than 22,000 subscribers. FTW reported on stories many mainstream news organizations overlooked. The organization dug deeper into CIA activities, reported Osama bin Laden’s ties with the American government in 1998, and broke a national story showing that then-Texas Governor George W. Bush routinely flew in an airplane once owned by drug smuggler Barry Seal. FTW obsessed over questionable government activities. This obsession led FTW to its biggest and most controversial story: the Bush administration’s involvement in the attacks of September 11th, 2001.

"As I watched the second plane strike the World Trade Center on September 11th, every part of me reacted," Ruppert would later write. Within hours of the attacks, Ruppert was on a radio show insinuating that 9/11 was an inside job. He became a forefather of the 9/11 Truth Movement — a loose contingent of activists speculating about the actual motives of the attackers and the government that day.

Ruppert mined websites, newspapers, and court records for evidence suggesting the Bush administration’s collusion in 9/11. The outcome was FTW’s defining article, "Oh Lucy! — You Gotta Lotta ‘Splainin To Do," an ongoing list of facts compiled from news stories, press conferences, and other disclosures. In Ruppert’s estimation, the piece "establishes CIA foreknowledge ... and strongly suggests that there was criminal complicity on the part of the US government." The list led Ruppert to publish his first book, 2004’s Crossing the Rubicon: The Decline of the American Empire at the End of the Age of Oil.

"THE US GOVERNMENT HAD DELIBERATELY LEAKED THE INFORMATION TO THE AL-QAEDA 'HIJACKERS' SO THAT THE ATTACKS COULD BE CARRIED OUT EFFECTIVELY."

At nearly 600 pages, not including endnotes and appendixes, Crossing the Rubicon is not a breezy read. But its core premise is fairly straightforward: the amount of oil available for human consumption peaked in the mid-’60s and has been quickly declining ever since (a concept known as "peak oil"). In order to reach the world’s precious remaining reserves, the US government was willing to perpetrate unthinkable acts.

According to Ruppert, then-Vice President Dick Cheney ignored warnings that hijacked planes might be used for terrorism in the US’ northeast corridor in the months leading up to September 11th. In May of that year, Cheney sent fighter planes from military bases in the northeastern US to Alaska. Ruppert concluded that the move was a calculated effort to leave the northeastern US vulnerable. Then, "the US government had deliberately leaked the information to the al-Qaeda ‘hijackers’ so that the attacks could be carried out effectively," Ruppert wrote. The ultimate goal: to start a war and secure unfettered access to Middle East oil.

Ruppert’s conclusions about 9/11 struck a nerve. His star rose, and FTW grew. Crossing the Rubicon became a cult hit. Ruppert was asked to give lectures all over the world, he said. By 2006, FTW supported Ruppert and a small staff in an office in Ashland, Oregon through sales of DVDs, donations, and an increasing number of subscriptions.

Ruppert and a fellow staffer work in the From The Wilderness offices in Ashland, Oregon.

But soon thereafter, FTW imploded. The organization’s offices were vandalized in June 2006. Ruppert initially told readers the break-in was "the work of an organized meth ring that I prevented from infiltrating my business." Later, the implications became more sinister. Ruppert suggested the meth ring was connected to the CIA. Either way, Ruppert told staff, friends, and readers, his life was in danger. In July 2006, he fled to Caracas, Venezuela, where he planned to report about life under Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez Frias.

But he likely had more sordid reasons for fleeing. In the months prior to his departure, Ruppert had grown fond of a new female hire — according to court records, Ruppert "said he was ‘in love’ with [the female staffer] and told her he was willing to have a ‘sexual relationship … if that’s what she wanted.’" The staffer wasn’t interested. Rather, she "felt shocked and scared" by his advances. After Ruppert fired her in June 2006, she filed a sexual harassment lawsuit against FTW. Among the allegations:

One evening in mid-May when Complainant [the female staffer] and Ruppert were alone in the office, Ruppert began complaining that he had a story he needed to get out, that he needed to free himself, and that it would be great if he could just run around the office naked for a minute to get out his "writer’s block." Shortly afterward, Complainant was typing at her desk and Ruppert came to her open door, standing in his underwear in a "wide legged stance" with a "big smile."

Before he left for Venezuela, Ruppert made allegations to anyone who would listen — including a reporter at a local newspaper in Ashland — that the staffer was a "sexual smorgasbord who engaged in sexual blackmail" and that it was actually she who had burglarized FTW’s offices. He also accused her of "being a meth addict and facilitating the use of [his] office to smuggle meth." None of these assertions were ever supported by police findings. A judge fined FTW $125,000 in damages in the case. But by the time that decision was reached in 2009, FTW had long ago ceased operations. The fine remains unpaid.

Carolyn Baker, a frequent guest on Ruppert’s podcast "The Lifeboat Hour" and now the show’s host, shared many of Ruppert’s fundamental beliefs. But Baker told me she also noticed Ruppert’s pattern of fleeing difficult situations. "My thought was, ‘Why can’t you just put on your big-boy pants, and run a company?’" she told me on a Skype call last month. "He couldn’t run From The Wilderness — he had to leave. And who knows if his life was in danger? … My conclusion was that he couldn’t deal with conflict," Baker said. "Whenever things got really hot in terms of conflict for Mike, he was like, ‘I’m out of here.’"

After four months in Venezuela, Ruppert fled there, too. He said he had been poisoned — perhaps at the hands of government operatives. That may have been true (his friends told me he emerged from Venezuela very sick; Ruppert’s lawyer, Wes Miller, described him as "a total fucking mess"). But Baker offered an alternative explanation: after asking her and another colleague to take over FTW — and granting them access to more than $20,000 in the company’s bank account — Ruppert squandered the entire reserve. "He was out of money," Baker told me. "He was like a sieve with money."

Jenna Orkin, an FTW contributor, housed Ruppert in her Brooklyn home upon his arrival in late 2006. They became lovers, and Orkin helped Ruppert through psychiatric treatments at Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan for depression and suicidal thoughts. Orkin told me over the phone that Ruppert was adept at what she called "public relations" — bending stories to his interpretation of reality. Oftentimes, that interpretation didn’t conform with the real world.

Gary Webb — the journalist behind "Dark Alliance," the series that proved so pivotal in Ruppert’s evolution — said as much in an interview with the Boston Globe in 2003: "Mike is a real conundrum. I think he’s a sincere guy, concerned about the right things, and he was quite supportive of my efforts to expose the interplay between the CIA and drug traffickers. But he’s also written stories expounding a theory about the genesis of my Mercury News series that were, quite frankly, ridiculous."

The US Department of Justice had long ago come to a similar conclusion. After Ruppert’s public appearance at the town hall meeting with the director of the CIA, it sent investigators to meet with Ruppert and dig into his accusations about Teddy, the CIA, and the LAPD. The investigators concluded that "while Ruppert communicates his allegations fervently, they have no firm anchor in reality."

It wasn’t long after FTW’s closure and Ruppert’s sojourn to Venezuela that director Chris Smith — the man behind documentaries American Movie and The Yes Men — contacted Ruppert to be interviewed for a film. The subject was supposed to be the CIA’s connections to drug smuggling, Smith told Indiewire. But Ruppert didn’t want to talk about the CIA. Instead, he wanted to talk about peak oil, and its critical implications for the future.

Ruppert told Smith he’d become convinced that the places we live, the cars we drive, the products we buy, the food we consume — the habits that shape industrial human civilization — were leading to our demise. Smith was intrigued. The resulting interviews in late March and early April 2009 became Collapse, a dark, ominous documentary. The film compiled some of the most intriguing facts Ruppert had amassed during his career, along with some of his most dire predictions. Among them: the imminent end of human industrial civilization. Ruppert made "Michael Moore sound like Mr. Rogers," said one reviewer.

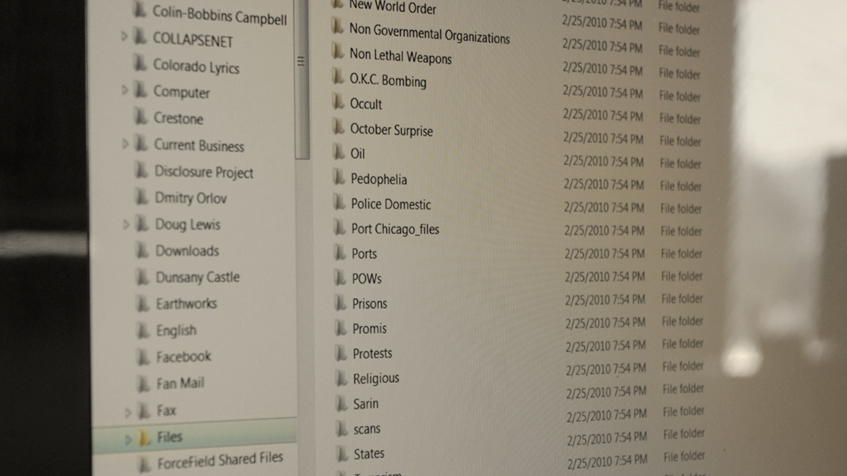

Collapse was well-received and brought Ruppert’s face and message to a wider audience. With his newfound notoriety, Ruppert and a few colleagues built CollapseNET— a reboot of FTW that focused squarely on peak oil and the end of human industrial civilization.

The unbelievable life and death of Michael C. Ruppert

After decades of struggle, the notorious doomsayer finally found fame and recognition. Then he shot himself.

By the second Sunday of April this year, Michael C. Ruppert was broke. The 63-year-old cop-turned-writer and firebrand gained fame by starring in Collapse, a 2009 documentary in which he predicts society’s destruction. Publicity from the film was great — he went on a countrywide promotional tour — but compensation had fizzled out. By April, he was receiving just a couple hundred dollars per month in royalties to supplement his meager Social Security checks.

In an effort to simplify his life, Ruppert had gradually sold, tossed out, or given away nearly all of his possessions, which included an arsenal of guns, countless books, and government documents. All that remained was a collection of sentimental knickknacks, along with clothes appropriate for a man in his 60s: button-up shirts, dark-colored slacks, a few flannels, a couple of L.L. Bean jackets, and a gray cowboy hat. Everything he owned fit into his burgundy 2000 Lincoln Continental.

For the last eight years, Ruppert had largely lived off the goodwill of friends and followers. When he made public requests for money — either through his weekly podcast, “The Lifeboat Hour,” or in posts to more than 5,000 Facebook followers — he received checks in the mail. When he needed a place to stay, people opened their homes. And it’s no surprise why: to subscribers of his elaborate theories — that the CIA trafficked drugs; that the Bush administration was behind the 9/11 attacks; or that the human race will face extinction by 2030 — Ruppert was a soldier who fought under the banner of truth. In exchange for exposing dark secrets, he was persecuted by authorities and shadowy organizations: he’d received death threats — both explicit and covert, he said — because he knew too much.

So when he made a plea for a place to stay early this year, a follower and friend named Jack Martin in Calistoga, California, offered up a modest trailer. That’s where, on the evening of April 13th, Ruppert committed suicide with a gunshot to the head. According to Ruppert’s friends, his suicide at first seemed sudden and unexpected — a brash decision during a dark moment. But looking back over his life and final days, Ruppert’s suicide resembles a grand finale — the end of a trail he’d been following for decades.

An only child, Ruppert’s family had close ties to the military and federal government. His father was a US Air Force pilot during the Second World War and later worked for Martin Marietta — which became Lockheed-Martin — "as a liaison between the CIA, the US Air Force, and Martin for booster programs," Ruppert wrote in a 2010 online autobiography.

Ruppert interviewed to be a CIA operative during his senior year at UCLA in 1973, he wrote, but turned down the subsequent offer. He became a cop with the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) and handled narcotics cases in some of the city’s most dangerous neighborhoods. The hours were long, and the job eventually got to him. He would later write that his work with the LAPD saddled him with "combat fatigue."

It was during his tenure at the LAPD that Ruppert met a woman named Nordica Theodora "Teddy" D’Orsay. Ruppert later wrote that their 15-month relationship "determined the course of my life…."

Teddy wasn’t a cop, but she and Ruppert met at a Marina del Rey cop bar in 1975. The two became infatuated with one another, and quickly moved in together. Early in their relationship, however, Ruppert became suspicious of Teddy. For a civilian, she was, he thought, a little too knowledgeable about guns and stakeouts and the day-to-day work of officers on a beat. She dropped names of LAPD cops as well as crime bosses and undercover agents.

When Teddy started staying out several nights per week and taking trips to San Francisco and Hawaii, Ruppert’s suspicions mounted. He treated Teddy as though she were a suspect in a crime. He gathered intel. It’s unclear what evidence he compiled, but Ruppert concluded that Teddy had ties to a San Francisco mobster and the shah of Iran. She grew even more distant. Then, in early 1977, she walked out on him.

After she left, Ruppert said, he became the victim of harassment: phone calls with dead silence on the other end; apartment searches while he was out; cars tailing him. He began sleeping with a gun under his pillow.

HE BECAME THE VICTIM OF HARASSMENT: PHONE CALLS WITH DEAD SILENCE ON THE OTHER END; APARTMENT SEARCHES WHILE HE WAS OUT; CARS TAILING HIM. HE BEGAN SLEEPING WITH A GUN UNDER HIS PILLOW

Ten weeks later, Teddy finally called Ruppert and said that she was in the New Orleans area. Ruppert drove to Louisiana and found her, he later wrote, "equipped with a scrambler phone and night-vision devices, and working from sealed communiqués delivered by Naval and Air Force personnel." He concluded that "she was involved in something truly ugly" — "arranging for large quantities of weapons to be loaded onto ships leaving for Iran." She was also working with "associates" of a New Orleans mafia boss bringing "large quantities of heroin into the city." Ruppert would later say that he and Teddy had even been shot at outside a New Orleans-area bar — retribution, he concluded, for discovering too much about Teddy’s covert actions. Ruppert broke off the relationship and returned home.

When he shared what he’d discovered with LAPD intelligence officers, they "promptly told me that I was crazy," he wrote. Overwhelmed, he checked himself into a psychiatric hospital for a "much-needed" monthlong rest. Though he was eventually reinstated as an officer, both his reputation and interest in the job vanished. In November 1978, he resigned. In time, Ruppert came to believe that the LAPD was part of a larger narco-trafficking network.

Through the press, Ruppert tried to expose what he’d discovered. In 1981, he made persistent calls to a Los Angeles Herald-Examiner columnist in an effort to expose Teddy’s trafficking network. The columnist ultimately published a two-part series, "The Spy Who Loved Me." But the series’ findings were, at best, inconclusive. It cited "a retired LAPD intelligence officer, another FBI agent, and [a psychiatrist]" who agreed that Ruppert’s story may have been "what he believes to be the truth," but that there was scant evidence to prove it. "Each of these three professionals professed both a measure of admiration and a measure of fear of Ruppert," the series read.

With paltry professional prospects, Ruppert drifted. He worked at a 7-Eleven, but was fired on his first day for selling alcohol to a minor. He declared bankruptcy and moved in with his parents. He developed a drinking problem. By 1984, he began attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and got sober. But he still struggled to find a new career. He told friends that he held a number of disparate jobs: as an amplifier assemblyman, a UPS driver, a gun shop clerk, a manager for a private security firm. In his spare time, he worked as a freelance writer — even landing a 1985 byline in the Los Angeles Times. In 1994, at the age of 43, Ruppert met a 23-year-old woman, Mary, at an AA meeting. The two got married — his first and only marriage — but divorced less than two years later. Distraught and aimless, he told Mary he was suicidal.

Then, Ruppert read a story that would change his life. It was a groundbreaking investigative report — a series of articles connecting the CIA to Nicaraguan drug runners. Published in August 1996 in the San Jose Mercury News, Gary Webb’s three-part series, "Dark Alliance," provided compelling evidence that drug traffickers peddled cocaine on Los Angeles streets to fund CIA-supported Contras embroiled in a Nicaraguan civil war. The series’ assertions — that CIA officials aligned themselves with criminals and "helped spark a crack explosion in urban America" — inspired protests in black communities nationwide.

HE WORKED AT A 7-ELEVEN, BUT WAS FIRED ON HIS FIRST DAY FOR SELLING ALCOHOL TO A MINOR. HE DECLARED BANKRUPTCY AND MOVED IN WITH HIS PARENTS. HE DEVELOPED A DRINKING PROBLEM

"Dark Alliance" drew harsh criticism for overreaching in its conclusions from several national outlets, including the New York Times. But that mattered little to Ruppert. In his eyes, Webb provided credible evidence that the CIA was involved in drug trafficking: "Dark Alliance" legitimized his accusations against Teddy, the CIA, and the LAPD.

The uproar over "Dark Alliance" was also an opportunity for Ruppert to have his suspicions heard. In November 1996, CIA director John M. Deutch agreed to address the allegations in Webb’s series during a town hall meeting at a high school in South Los Angeles. The interaction was broadcast by C-SPAN, and Ruppert seized the opportunity to step into the spotlight.

"I am a former Los Angeles police narcotics detective, and I worked South-Central Los Angeles," Ruppert said into a microphone during the Q&A session in front of the jam-packed, audibly agitated, mostly African-American crowd. In the video — now legendary among Ruppert’s fans — Ruppert looks like a high-school social studies teacher, with combed-over gray hair, a manicured mustache, and wire-rimmed glasses. "I will tell you, Director Deutch," Ruppert said, "emphatically and without equivocation that the agency has dealt drugs throughout this country for a long time."

"THAT’S WHAT I DID 18 YEARS AGO, AND I GOT SHOT AT FOR IT."

The audience erupted. When the din subsided, Deutch suggested that Ruppert report his findings to the authorities. "That’s what I did 18 years ago, and I got shot at for it," Ruppert said, referencing the alleged shooting incident with Teddy outside a New Orleans-area bar.

The crowd jeered Deutch. Ruppert looked on with a satisfied grin. In a matter of minutes, he had become a heroic figure battling the CIA, willing to stare down authority.

News of the confrontation spread, and Ruppert capitalized on the publicity. He started a muckraking, conspiratorial newsletter called From The Wilderness (FTW) that would eventually boast more than 22,000 subscribers. FTW reported on stories many mainstream news organizations overlooked. The organization dug deeper into CIA activities, reported Osama bin Laden’s ties with the American government in 1998, and broke a national story showing that then-Texas Governor George W. Bush routinely flew in an airplane once owned by drug smuggler Barry Seal. FTW obsessed over questionable government activities. This obsession led FTW to its biggest and most controversial story: the Bush administration’s involvement in the attacks of September 11th, 2001.

"As I watched the second plane strike the World Trade Center on September 11th, every part of me reacted," Ruppert would later write. Within hours of the attacks, Ruppert was on a radio show insinuating that 9/11 was an inside job. He became a forefather of the 9/11 Truth Movement — a loose contingent of activists speculating about the actual motives of the attackers and the government that day.

Ruppert mined websites, newspapers, and court records for evidence suggesting the Bush administration’s collusion in 9/11. The outcome was FTW’s defining article, "Oh Lucy! — You Gotta Lotta ‘Splainin To Do," an ongoing list of facts compiled from news stories, press conferences, and other disclosures. In Ruppert’s estimation, the piece "establishes CIA foreknowledge ... and strongly suggests that there was criminal complicity on the part of the US government." The list led Ruppert to publish his first book, 2004’s Crossing the Rubicon: The Decline of the American Empire at the End of the Age of Oil.

"THE US GOVERNMENT HAD DELIBERATELY LEAKED THE INFORMATION TO THE AL-QAEDA 'HIJACKERS' SO THAT THE ATTACKS COULD BE CARRIED OUT EFFECTIVELY."

At nearly 600 pages, not including endnotes and appendixes, Crossing the Rubicon is not a breezy read. But its core premise is fairly straightforward: the amount of oil available for human consumption peaked in the mid-’60s and has been quickly declining ever since (a concept known as "peak oil"). In order to reach the world’s precious remaining reserves, the US government was willing to perpetrate unthinkable acts.

According to Ruppert, then-Vice President Dick Cheney ignored warnings that hijacked planes might be used for terrorism in the US’ northeast corridor in the months leading up to September 11th. In May of that year, Cheney sent fighter planes from military bases in the northeastern US to Alaska. Ruppert concluded that the move was a calculated effort to leave the northeastern US vulnerable. Then, "the US government had deliberately leaked the information to the al-Qaeda ‘hijackers’ so that the attacks could be carried out effectively," Ruppert wrote. The ultimate goal: to start a war and secure unfettered access to Middle East oil.

Ruppert’s conclusions about 9/11 struck a nerve. His star rose, and FTW grew. Crossing the Rubicon became a cult hit. Ruppert was asked to give lectures all over the world, he said. By 2006, FTW supported Ruppert and a small staff in an office in Ashland, Oregon through sales of DVDs, donations, and an increasing number of subscriptions.

Ruppert and a fellow staffer work in the From The Wilderness offices in Ashland, Oregon.

But soon thereafter, FTW imploded. The organization’s offices were vandalized in June 2006. Ruppert initially told readers the break-in was "the work of an organized meth ring that I prevented from infiltrating my business." Later, the implications became more sinister. Ruppert suggested the meth ring was connected to the CIA. Either way, Ruppert told staff, friends, and readers, his life was in danger. In July 2006, he fled to Caracas, Venezuela, where he planned to report about life under Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez Frias.

But he likely had more sordid reasons for fleeing. In the months prior to his departure, Ruppert had grown fond of a new female hire — according to court records, Ruppert "said he was ‘in love’ with [the female staffer] and told her he was willing to have a ‘sexual relationship … if that’s what she wanted.’" The staffer wasn’t interested. Rather, she "felt shocked and scared" by his advances. After Ruppert fired her in June 2006, she filed a sexual harassment lawsuit against FTW. Among the allegations:

One evening in mid-May when Complainant [the female staffer] and Ruppert were alone in the office, Ruppert began complaining that he had a story he needed to get out, that he needed to free himself, and that it would be great if he could just run around the office naked for a minute to get out his "writer’s block." Shortly afterward, Complainant was typing at her desk and Ruppert came to her open door, standing in his underwear in a "wide legged stance" with a "big smile."

Before he left for Venezuela, Ruppert made allegations to anyone who would listen — including a reporter at a local newspaper in Ashland — that the staffer was a "sexual smorgasbord who engaged in sexual blackmail" and that it was actually she who had burglarized FTW’s offices. He also accused her of "being a meth addict and facilitating the use of [his] office to smuggle meth." None of these assertions were ever supported by police findings. A judge fined FTW $125,000 in damages in the case. But by the time that decision was reached in 2009, FTW had long ago ceased operations. The fine remains unpaid.

Carolyn Baker, a frequent guest on Ruppert’s podcast "The Lifeboat Hour" and now the show’s host, shared many of Ruppert’s fundamental beliefs. But Baker told me she also noticed Ruppert’s pattern of fleeing difficult situations. "My thought was, ‘Why can’t you just put on your big-boy pants, and run a company?’" she told me on a Skype call last month. "He couldn’t run From The Wilderness — he had to leave. And who knows if his life was in danger? … My conclusion was that he couldn’t deal with conflict," Baker said. "Whenever things got really hot in terms of conflict for Mike, he was like, ‘I’m out of here.’"

After four months in Venezuela, Ruppert fled there, too. He said he had been poisoned — perhaps at the hands of government operatives. That may have been true (his friends told me he emerged from Venezuela very sick; Ruppert’s lawyer, Wes Miller, described him as "a total fucking mess"). But Baker offered an alternative explanation: after asking her and another colleague to take over FTW — and granting them access to more than $20,000 in the company’s bank account — Ruppert squandered the entire reserve. "He was out of money," Baker told me. "He was like a sieve with money."

Jenna Orkin, an FTW contributor, housed Ruppert in her Brooklyn home upon his arrival in late 2006. They became lovers, and Orkin helped Ruppert through psychiatric treatments at Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan for depression and suicidal thoughts. Orkin told me over the phone that Ruppert was adept at what she called "public relations" — bending stories to his interpretation of reality. Oftentimes, that interpretation didn’t conform with the real world.

Gary Webb — the journalist behind "Dark Alliance," the series that proved so pivotal in Ruppert’s evolution — said as much in an interview with the Boston Globe in 2003: "Mike is a real conundrum. I think he’s a sincere guy, concerned about the right things, and he was quite supportive of my efforts to expose the interplay between the CIA and drug traffickers. But he’s also written stories expounding a theory about the genesis of my Mercury News series that were, quite frankly, ridiculous."

The US Department of Justice had long ago come to a similar conclusion. After Ruppert’s public appearance at the town hall meeting with the director of the CIA, it sent investigators to meet with Ruppert and dig into his accusations about Teddy, the CIA, and the LAPD. The investigators concluded that "while Ruppert communicates his allegations fervently, they have no firm anchor in reality."

It wasn’t long after FTW’s closure and Ruppert’s sojourn to Venezuela that director Chris Smith — the man behind documentaries American Movie and The Yes Men — contacted Ruppert to be interviewed for a film. The subject was supposed to be the CIA’s connections to drug smuggling, Smith told Indiewire. But Ruppert didn’t want to talk about the CIA. Instead, he wanted to talk about peak oil, and its critical implications for the future.

Ruppert told Smith he’d become convinced that the places we live, the cars we drive, the products we buy, the food we consume — the habits that shape industrial human civilization — were leading to our demise. Smith was intrigued. The resulting interviews in late March and early April 2009 became Collapse, a dark, ominous documentary. The film compiled some of the most intriguing facts Ruppert had amassed during his career, along with some of his most dire predictions. Among them: the imminent end of human industrial civilization. Ruppert made "Michael Moore sound like Mr. Rogers," said one reviewer.

Collapse was well-received and brought Ruppert’s face and message to a wider audience. With his newfound notoriety, Ruppert and a few colleagues built CollapseNET— a reboot of FTW that focused squarely on peak oil and the end of human industrial civilization.

Last edited: